The Three Levers Changemakers Must Pull to Eliminate the Racial Wealth Gap

This is the second post in our Future of Black Wealth content series. To read the first post, click here.

As Arabella Advisors was working to open our newest office in Durham, North Carolina earlier this month, we used a co-working space in a building that also houses North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company. NC Mutual Life is the oldest and largest African American life insurance business in the world. Sharing a space with such a historically significant enterprise is not only inspiring, it’s also been a fortuitous opportunity to learn from and observe the parallels between NC Mutual’s approach to community development and our own recent work to close the racial wealth gap.

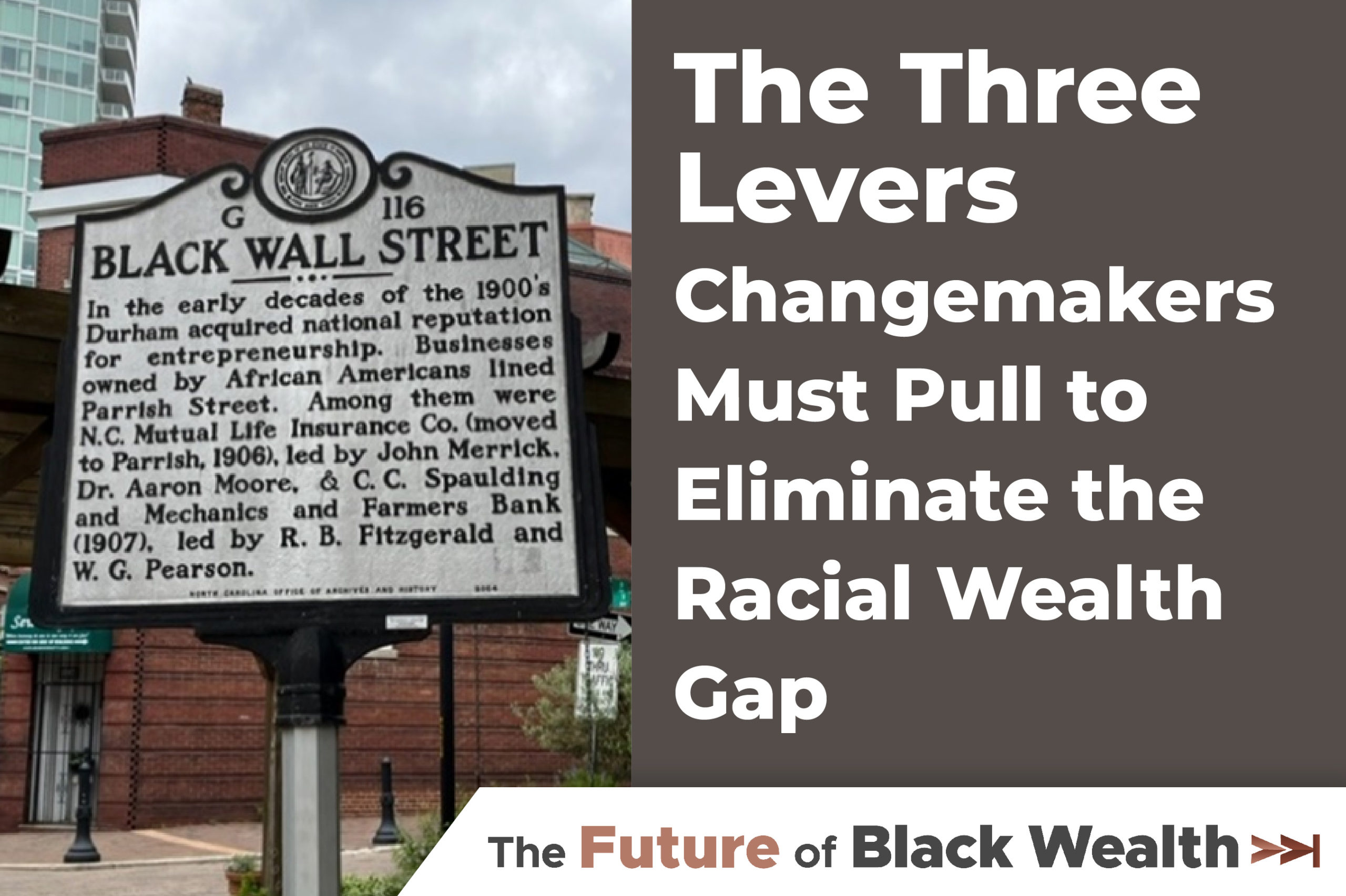

The company formulated the concept of the Double Duty Dollar—a belief that income from insurance sales could be redeployed back to the community via investments in jobs, loans, and social programs and policies. NC Mutual also helped to give rise to Durham’s Black Wall Street, known during Reconstruction as fostering Black entrepreneurship. Right next door to Black Wall Street was Hayti, founded as an independent Black community by freedmen coming to work in tobacco warehouses at the end of the Civil War. At its peak, there were 200 Black-owned businesses in Hayti.

Durham was a showcase for how the mutually reinforcing pillars of capital, philanthropy, and policy were the bedrock for building wealth for Black communities and individuals. I say “was” because the model didn’t come to full fruition. The pillars were sound, but race-based urban redevelopment, biased zoning laws, and the systematic disenfranchisement of Black voters in the mid-20th century led ultimately to the demise of the community of Hayti and the businesses that once flourished there.

The story of Durham has been repeated in communities such as Greenwood, Rosewood, and elsewhere, serving as a model for how to build wealth in Black communities but also, sadly, as examples of how others in those communities viewed that wealth and self-sufficiency as existentialist threats. How can donors best learn from these past models while preventing the same kind of backlash? Recent efforts to move toward a true racial reckoning have surfaced a wide range of ideas, including early-stage angel and venture capital funds to support Black entrepreneurs, pooled grantmaking funds to support BIPOC people and communities, corporate philanthropy efforts that build financial capability and inform public policy, and advisory solution sets on race and wealth from large and small consultancies. While each of these interventions can help close the racial wealth gap, none is the complete answer that each has claimed to be. Most aim at discrete parts of an ecosystem-level problem that is both enormous and enormously complex. On their own, these ideas simply aren’t a match for the scale and complexity of this problem.

Over the past two decades, our work with a wide range of donors, impact investors, advocates, and changemakers has taught us that challenges of this magnitude typically require coordinated interventions that combine the tools of philanthropy, impact investing, and policy advocacy. This challenge is a clear case-in-point: No one factor or system was responsible for creating the societal fissures that led to the racial wealth gap—nor for continuing to widen it. Thus, we need to pull all levers available to us in order to adequately tackle the intersecting systems of oppression and widespread systemic racism that perpetuate it.

The first lever is effective, efficient, and equitable grantmaking—that is, philanthropy as it can and should be practiced today. Routine grantmaking is the bread-and-butter of an integrated strategy, and it provides a distinctive opportunity for donors to deliver dollars to grassroots, high-impact, BIPOC-led and BIPOC-serving organizations. Grantmaking allows capital to flow in support of essential services, and grants are an effective way to de-risk innovative investments and catalyze additional investment in proven models. In this way, donors can seed new ideas and test solutions that could be scaled through other funding streams or public policy, such as baby bonds.

Given that closing the racial wealth gap is about wealth creation, impact investing is also a critical lever. It’s a way to support entrepreneurs of color who face bias in fundraising, reduce the cost of capital for Black- and other people of color-owned businesses, or solve market failures by using different-in-kind financing instruments. Since capital has for so long been denied to Black entrepreneurs, and predatory lending practices continue to target Black individuals, there is significant distrust among these communities in traditional financial institutions and a lack of confidence in traditional lending and equity practices. Thus, impact investing may be a more viable pathway for building trust with communities—assuming the investors do the hard work of examining their practices and rooting out biases that may perpetuate inequities.

Grantmaking and impact investing are essential, but alone, they aren’t enough. Too many of our systems—from the criminal justice system to education to legalized, discriminatory business practices—have methodically excluded Black and other communities of color from opportunities to build wealth. Thus, to effectively address the racial wealth gap, we must acknowledge, interrogate, and strategically reform these systems. This means enshrining our desired reforms in more just laws, regulations, policies, and practices across a variety of fields, including real estate, health care, banking, and more.

We’re convinced it is the combination of these activities in an integrated strategy—not any one of these activities in isolation—that will accelerate closing the racial wealth gap and bolstering Black wealth in particular. Additionally, a crucial component of an integrated strategy, across all three levers, is narrative change, as we must shift stubborn mindsets and dismantle the harmful assumptions that currently enable these systems to continue hoarding opportunity from people of color. Eliminating racial gaps across the economy is not only about righting historic wrongs. It is also about choosing a more dynamic future in which a group of people prohibited from achieving their full potential can flourish.

In subsequent posts in our Future of Black Wealth series, we’ll dive more deeply into each of these three crucial levers to explore how donors and other changemakers can effectively deploy these tactics to create real reform. Don’t miss a post; keep up with the content series here. Or you can get connected with us here.